Last Updated on June 27, 2022 by Laura Turner

Students may not be aware of the variety of opportunities available within the Indian Health Service (IHS). To learn more about IHS and the volunteer, scholarship, and employment opportunities available, the Student Doctor Network recently spoke with Dr. Charles North, retired Chief Medical Clinical Officer for Indian Health Services.

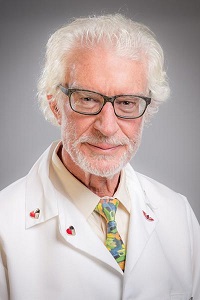

Charles North attended medical school at the University of Pittsburgh and completed his residency at the University of Minnesota. Currently, he serves as Professor of Family and Community Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine.

Would you explain what the Indian Health Service is?

Gladly. The Indian Health Service (www.ihs.gov) is an agency within the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Since IHS is designated as an agency or “Operating Division” within HHS, it is a parallel organization to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and several others.

The IHS was created in 1955 when Congress transferred responsibility for health of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the federal department that preceded HHS. The IHS is the principal federal health care provider and health advocate for Indian people.

The mission of the IHS, in partnership with Native American and Alaska Native people, is to raise their physical, mental, social, and spiritual health to the highest level.

The goal is to ensure that comprehensive, culturally acceptable, personal and public health services are available and accessible to all Native Americans and Alaska Native people.

The foundation of the Indian Health Service is to uphold the Federal Government’s obligation to promote healthy Native American people, communities, and cultures and to honor and protect the inherent sovereign rights of Tribes. It is charged with providing direct medical care in the broadest sense, elevating their health status to the highest level possible.

Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in 1975 to provide Tribes the option of assuming from the IHS the administration and operation of health services and programs in their communities, or to remain within the IHS-administered direct health system.

The IHS has around 15,000 employees and Tribes probably employ about an equal number of tribal employees. Over 70% are Native Americans or Alaska Natives. There are about 1,000 physician positions in the system, about half of whom are primary care physicians. As of July 2009, 21% of the physician positions were vacant.

There are 35 states that have significant Native American populations and/or reservations, mostly in the western United States and Alaska. About half of the health care for Native American and Alaska native populations is administered by the tribes and reservations themselves and half by the “feds” (i.e., directly by the federal IHS).

The Indian Health Service might be an appropriate career path for certain health professional students. Is this mainly a program for students who are from Native American communities, or is it open to any qualified health professional?

The IHS’ first priority is to the Native students themselves. We have a scholarship program for Native students and Native American preference for all federal positions.

But there is a shortage of qualified Native students, with not enough people in training to meet the projected need of the rapidly growing population. Even though there has been a steady increase in numbers, we do not expect that Native students will be able to meet the human resource needs of either the IHS or tribal programs in the foreseeable future.

What type of background do you look for in the IHS and whom do you think would find this an appealing career?

The most successful students are those oriented towards working with service to underserved populations, who enjoy cross-cultural and “transcultural” experiences, who have a special appreciation for an Native American or Alaskan Native community, or who want to work with indigenous people.

If you have a background working in the Peace Corps, or AmeriCorps, or have done missionary work, you may be attracted to the populations and communities that the IHS serves.

Say you are a college student interested in pre-med or in one of the health professions. How would you get information about eligibility for the scholarship programs?

There is a national IHS office in Rockville, Maryland that helps anyone interested in scholarships. However, the criteria for scholarships are quite rigorous. Most of these opportunities would be for enrolled members of tribes. If you are in this category, one’s tribal administration or the Rockville office can guide you through the application processes.

The Native Health Initiative funds summer health and justice internships. The IHS does provide some opportunities nationally in the Commissioned Officer Student Training and Extern Program (COSTEP) that lead to early commissioning in the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Officer Corps and provide exposure to health professionals in federal agencies, including the Indian Health Service Commissioned Officer Corps.

Are there experiences for baccalaureate students on Indian reservations and other places?

Several reservations and tribal clinics have developed programs, such as the “health and justice” initiatives mentioned above. An interested person should contact a local site. There may be a volunteer program that would suit your interests and background. I am aware that anthropology majors, linguistics majors – even persons interested in law enforcement – have found things to do on some reservations. Undoubtedly, an experience of this kind early in one’s education might reinforce an early interest in this kind of service.

I would expect that there are more opportunities for students who are already enrolled in health professions schools?

Yes, such students have several options. The summer COSTEP program mentioned above requires that one signs up for the commissioned corps. We get a lot of students. Most of the interest is from pharmacy and engineering programs, but other health professionals are eligible.

Many of the schools in the 35 states with federally recognized Tribes have relationships with IHS and Tribal sites. Some programs in Alaska will pay room and board and airfare to get students to remote Alaskan communities.

Other programs will cover transportation and room and board for fourth-year medical school elective rotations. You should check with your school and see if there are options for you to work in Indian Health facilities.

In Albuquerque, the IHS has a formal affiliation with the University of New Mexico. One of its Tribal sites takes students from all over the country. The Navajo, Tucson, and Phoenix IHS Areas in the Southwestern United States also take students from throughout the nation.

Oklahoma has many local affiliations, so there are many opportunities there. The Northern Plains, Montana, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Washington State regions all have some active and dynamic relationships. Check with your school.

How did you personally decide on a career in the Indian Health Service?

I was interested in service to needy populations even when before I was a medical student at the University of Pittsburgh. After taking a senior-year elective in preventive medicine on the Navajo reservation, I entered a residency at the University of Minnesota and took an “outstate” (rural) rotation in Cass Lake, Minnesota, home of the Leech Lake Ojibway.

At that time, having a residency rotation at a remote Indian Health Service site was considered so different an experience that my University of Minnesota department chair and several professors flew up to Cass Lake to see it. If you are a student or resident and want to do something like this, check with your school. Most likely you have faculty that are IHS veterans. The school may work something out with you.

Are there particular lifestyle interests that you find to make a good match?

Generally, people who like to live in rural areas may find this is a good fit. Those people who love riding horses, rodeos, backpacking into “frontier” areas, mountain biking, long-distance running, skiing, fishing, hunting, and so on often find the rural and frontier IHS settings attractive.

But for those who are oriented to urban life, you could live in a city and work at an Indian Health urban or rural site. It is a fact that over 50% of the Indian population lives in urban areas. Urban Native American programs exist in some of the largest cities in the US. For some specialties, the only positions that exist are at the urban sites.

Besides the scholarship program for Indian students, do you have “loan repayment for service” programs?

The IHS has a loan repayment program, similar to the federal Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) National Health Service Corps program for community health centers. It has been funded at a lower level than the need, but it is quite possible that there may well be more money allocated to this program in the future.

It currently is set at $20,000 a year covering all the health professions, not just physicians. Because of the financial resources of some of the tribal sites, such as the Navajo, there are supplemental funds for loan repayment. One should check with local sites.

In the IHS, to date, loan repayment has been used mainly for retention, rather than recruitment. Stay tuned on loan repayment, as this may be augmented in this era where health care reform is a legislative priority. There are a number of IHS Native American Health centers sites that get HRSA “Section 330” funding – a principal program for funding community health centers. They may be eligible for the HRSA loan repayment program for either an urban Native American or Tribal site.

Not every person who went through the University of Pittsburgh medical school chose careers in the Indian Health Service. How did you get interested in this field?

I grew up in Seattle and observed that Native people there had both lower health status and lower socioeconomic status. I was interested in civil rights and social justice. I met Native students in college and found we had many interests in common.

When I went to medical school in Pittsburgh, they had an elective on the Navajo reservation rotation for fourth-year medical students. I went to a preceptorship at Fort Defiance, Arizona, where I worked in the hospital, clinic, and community health program and did some epidemiological research.

Personally, I love the Southwest and liked working with tribal people, feeling that I was responding to a tremendous demand for health services. I found that the IHS healthcare services were extremely well organized into a rational system, unlike most of the rest of the country.

The IHS integrates public health and primary health care in such a way that one could make a difference quickly in meeting healthcare needs. I found this system of community-oriented primary care very satisfying compared to private practice. Then I did a third-year residency rotation in Minnesota and found that the system there was very similar and comfortable for me.

I loved the IHS system that existed in both Fort Defiance and Cass Lake. The population needs far exceed our ability to meet them, but I felt that I was fighting the right battle, that the organization’s core values were congruent with my core values. So after residency that is all I wanted to do.

I went to the Hopi Reservation in Keams Canyon, Arizona and served as a family physician, director of community health services and eventually became the chief executive officer of the health system there. The integration of public health and medicine in team programs made great sense. The health care team is much better developed in Native American health.

I’m full-time faculty and former Program Director at Santa Rosa’s Family Medicine Residency in Sonoma County California. At least a dozen of our graduates over the years have found very rewarding and satisfying positions at Indian Health Service sites in both rural and suburban locations, inside and outside California. They seem most satisfied with the broad scope of family medicine they are allowed to practice and the opportunity of caring for an underserved population.

Thanks for taking the time to write this article Dr. Burnett. I’ve been considering working at an IHS site in rural Arizona for 10+ years, as it seems like a great way to serve the underserved people. I am a foreign medical grad, and will apply for a residency next application cycle, but was wondering if there are any options for those out of medical school but not yet in a residency, foreign or US grads, to volunteer/shadow/work at an IHS site, such as the one at Fort Defiance?

Most IHS and Tribal sites only consider board certified and residency trained physicians, Matt. You may be able to volunteer in a community based program. I suggest you contact the Navajo and Phoenix Areas (regions) of the IHS and ask them directly. Good luck

Charles North

I haven’t met anyone who has worked for IHS that did not leave disgruntled and unappreciated. Myself included.

My wife is an ENT Specialist with about 18 years as a surgeon in Malaysia. She is a graduate of a prestigious medical college in India, and she is a citizen of that country. I am an American Citizen. We have been married for several years and are considering a move back to the US. She has not gone through the USMLE programs, but we have been advised that some Indian reservations may not have the same requirements as an “off the reservation” doctor’s office. Is this true? At her age, 54, including residency requirements after passing the USMLE, she may well be near 60, which doesn’t giver her much time to actually practice in the US. With her experience, qualifications, and training is it possible for her to be hired at an Indian reservation?

Hi Gary, how are you?

I’ in the same situation as your wife and have the same question. Could you tell me please if you had any respoces and found the way to avoid USMLE and do residency in US. Will be appreciate for any information.

Sincerely, Alexandr London

There is also opportunity to work at IHS facilities as a temp in different medical fields. For example, Indian Health Service experienced pharmacists have the opportunity to temp at federal or tribal facilities. Many pharmacists do it for the flexibility in their work. Some are retired pharmacy directors from the IHS who still want to contribute; others are new pharmacy grads who had a good experience during an IHS rotation. They all enjoy the flexibility & adventure. The pharmacists can work when they want to.

I’ve made a career out of working at different IHS pharmacies as a temp pharmacist. Now I get IHS-experienced pharmacists connected to travel assignments, because of the many connections I have within IHS.