Last Updated on June 26, 2022 by Laura Turner

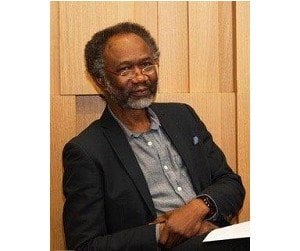

Dr Femi Oyebode is a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Birmingham and a published poet. He obtained his medical degree from the University of Ibadan (1977), followed by his MD at University of Newcastle, and his PhD in Wales (1998). In November 2016, he received a lifetime achievement award from the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

He is the author of the textbooks Sims’ Symptoms in the Mind: An Introduction to Descriptive Psychopathology, 4th Edition, Madness at the Theatre and Mindreadings: Literature and Psychiatry. He has also published 6 volumes of poetry, including Adagio for Oblong Mirrors; Master of the Leopard Hunt; and Indigo, Camwood and Mahogany Red.

When did you first decide to become a physician? Why?

I’m Nigerian by birth. I went to medical school in 1972, at the age of 18, and before that I went to boarding school where we had to choose our ‘O’ level subjects at the age of 13. We were streamed into Sciences or Arts subjects. In the sciences you were either in the stream that concentrated on mathematics, physics and chemistry or biology, physics and chemistry. So if you’re not particularly good at mathematics, you were likely to be headed for medical school. That’s just how it was. We’re talking about where and when I was educated. I’m not sure that I consciously made a decision before I did A-levels. I did my A-levels exams at the age of seventeen, so that would have been where I personally, consciously decided to aim for medicine.

How did you choose the medical school you attended?

The choices in my day were not extensive. There were five medical schools in Nigeria, and I knew I wanted to go to Ibadan. I also applied to University of Ife, but I was always going to go to Ibadan.

What surprised you the most about your medical studies?

I wouldn’t say anything did. Obviously, it is arduous and rigorous, so you have to work very hard, but there wasn’t anything unusual about the course itself.

What aspect of medicine informs your creative writing, if any?

None, per se. Obviously, there’s a lot of similarity between medicine and writing. You couldn’t be a good doctor without observational skills, the capacity to attend to other people, to observe what they look like, to attend to the language they’re using, to attend to how they’re sitting, in order to work out whether they are happy or unhappy, irrespective of what your specialty is. So that aspect of medicine is shared in common with creative writers’ attitude to the world: the capacity to observe properly how life is lived and to be aware of and interested in the inner life of people. Both fields share that in common. But I don’t write about psychiatry, and I certainly don’t write about medicine. So I think you could just say that I carry the same attitude to the world, and it informs my medical practice as well as my writing.

What led you to specialize in psychiatry?

If I hadn’t gone to medical school, I would have studied literature. When the time came to choose a specialty in medicine, it had to be something which would allow me to get as close to the humanities as possible. You could say that psychiatry was the closest medical specialty to the humanities. I also told myself that my specialty would be something I would do even if I wasn’t being paid. This helped me work out what my proper interests were. That’s how I ended up in psychiatry.

Tell me more about how you first got involved with creative writing.

Consciously, I’ve been writing since I was eight years of age. As far as I can remember, my mind has always worked in that way. My mind works in a way which tries to capture inner experience through the medium of words. To be truthful, that’s all there is to say about it. Some would say it’s like a gift, some would say it’s an inner urge. I’m not one of these people who suddenly thought: “I’d like to write”. I’ve always written.

There is a question about how you decide whether you’re going to be a poet or a fiction writer. Again, these different ways of expressing yourself in language choose you. I don’t think you choose them. I think that the basic difference is that the people who are poets are preoccupied with language, the way in which it works, the way in which words operate, the sounds of the words, the texture of the words, the materiality of words, what a line looks like. On the other hand, people who are interested in fiction are interested in storytelling. Of course, they have to handle the language well. But the purpose of their endeavour is to invent stories. I don’t think you wake up and say: I am going to be this. I couldn’t write a story, if I tried. I don’t go to bed thinking of a story, whereas I’m constantly working on how to describe the world that I inhabit with words, creating images that speak to my responses to the world. There’s a bit of storytelling, you’ve got to have a narrative drive, but I think that’s the difference. You’re not choosing it; I think these things are choosing you.

Has being a doctor met your expectations? Please explain.

Well, I’m still doing it! I’ve been practising medicine for 40 years this year, and I’m still enjoying it. And I’ve been in psychiatry for 39 of these years. As for the desired closeness to the humanities: on paper, you could argue that I’m a biological psychiatrist. I’m not a psychotherapist. I have an interest in how the brain works. I’m a psychopathologist; that’s what I do, that’s what I read and think about all the time. So I wouldn’t say these interests are especially close to the humanities, at least within psychiatry. However, the day-to-day practice of psychiatry – not the intellectual research or academic aspects – i.e. sitting in front of another human being, is as close to the humanities as one could hope for, as it’s totally embedded in language.

What do you like most about being a doctor?

It’s a privilege to do a job where you’re not doing harm; you’re doing good, or at least you’re trying to be helpful to other human beings. There aren’t many jobs like it on the planet, where you’re just trying to do good.

What do you like least about being a doctor?

At present, in the U.K., you’ve got the difficulties of resources, but that’s not a flaw with medicine itself; rather, it arises from the economic, political and social situations in which medicine is practised. If you’re practising in Africa, you might be very, very clever, but you may not be able to do the things you need to do, because the resources are insufficient. Even though the UK is a rich country, we’re nonetheless unable to do all the things we would like to do, which can be frustrating.

In your position now, knowing what you do, what would you say to yourself back when you started your medical career?

I am not sure there’s much advice I would give my 18 year old self. When you’re a 16/17-year-old, you have no knowledge of how the world works, so you can’t comment on that. I haven’t got any regrets. If you’re going into this profession, you’re going to have to work very, very hard. I might have told myself that it’s not an ordinary job; it’s a way of life. You see a patient, and you think about them all the time. One just didn’t know that it’s not an ordinary job at seventeen. But I don’t think a 17-year-old would have understood the difference between a job and way of life.

What do you like most about writing?

Of course, like with anything else, you get satisfaction if it works all right, if you reread something you’ve written, if someone else reads it and thinks it’s good. So there’s a satisfaction to do with completing the task, and you feel a sense of achievement.

What do you like least about writing?

A good way to think of a short story writer or a poet is that the material is relatively abbreviated so that you haven’t got the same issue of living with one idea over a prolonged period. I wouldn’t say that I find anything particularly frustrating. A fiction writer is living with an idea for prolonged periods, so they’re more inclined to end up in cul-de-sacs and there may be frustration if a work is stillborn because of the investment that has not come to fruition. If I were a novelist, it would be very, very difficult to do that alongside practising medicine the way I practise it. So I can’t say I’m frustrated particularly by any aspect of writing.

Describe a typical day as a doctor—walk me through a day in your shoes.

I’ve been in clinic all day. Today’s clinic started at 9:15 am, and ended at 5:15 pm with a 30 minute break for lunch. The patient population encompassed a variety of psychiatric conditions and an extraordinary range of social situations. Mondays and Tuesdays are all-day clinics. Mondays, I do general psychiatry. Tuesdays, I do perinatal psychiatry; I go to the women’s hospital and see pregnant women with psychiatric histories. Wednesdays, I do academic psychiatry: I’m involved with teaching, or reading, or thinking, or being involved in some research discussion. So at present, I do medical work 3 days a week.

I do the whole range of what an academic psychiatrist does. I write, I supervise others, or go to meetings where people present their work. I’m not doing a lot of empirical research these days. You could say that my focus is now on scholarly research.

Describe a typical day writing—walk me through a day in your shoes.

I’ve been working part-time for six years. Because of my age, I’ve now partly retired from medicine. As for writing, I’m writing all the time whether in my head or on paper. Tonight for example, I’ll go up to my study when I’ve had something to eat, and will probably work till midnight. You have to keep in mind I’m an academic, so I’m writing scientific as well as creative works. I’m writing the sixth edition of a psychopathology book, which has to be with the publishers by the end of September this year. So I’m currently constantly working on that. Of course, I’m writing and reading literature as well, but I’m not one of these very organized people who will tell you that they spend their Thursday night “doing literature”. I wish I was!

I’m not a writer who just writes out of inspiration, either. I’m currently working on a fairly long poem, and have been for 18 months. The inspiration is to do with the subject matter. The British invaded Benin in 1898, and the chronicler of the British invasion happened to be a doctor as well. I’m working from his diary about the invasion itself and the subsequent events which led up to the King being brought to court and exiled. Past the point of inspiration, I just need to work hard, to capture the experience of somebody else, to find the form of words to describe inner feeling, and to use all the resources of poetry to create what I hope will be beautiful and memorable even if troubling and tragic.

On average, how many hours a week do you work? How many weeks of vacation do you take annually?

I’m going to Berlin at the end of the week. My wife, also an academic, is speaking at a conference there, so I’ll go along for a long weekend. If I go to speak at a conference in Portugal or Italy, I’ll work, then we’ll try go to a museum. It’s a different kind of life. I don’t travel to go lie on a beach somewhere; it’s just not for me. But I am not proud of my schedule and I am not recommending it to anyone else.

How do you balance work and your life outside of work?

I’m not a young person, so my children are in their thirties. I’ve long passed the time when I had young children to look after. At present, my preoccupation is looking after our 2-year-old granddaughter every other Friday with my wife. Outside of that, I live off the arts: theatre, concerts, that sort of stuff. Everything in my life, apart from family, is geared towards medicine and literature. I was at a writer’s conference on Saturday, where I said that the work-life balance question is a modern question. In my life, there’s no difference between work and life. To some it looks like I’m working all the time, but I’m not complaining.

What types of outreach/volunteer work do you do?

I’m quite busy as is!

From your perspective, what is the biggest problem in healthcare today? Please explain.

For the first time in the history of Americans, they’re getting what the rest of us take for granted in Western Europe, in terms of healthcare. It’s very strange that you have a rich country that doesn’t care for its people. Healthcare is so fundamental, so we’re all preoccupied with how to make sure that everybody on the planet has access to relatively good healthcare. How you deliver that is a different issue, but it ought to be delivered in such a way that not only the rich can have it. Not all doctors are preoccupied with it, but if you’re a thoughtful person, you ought to be.

What is your final piece of advice for students interested in pursuing a career in psychiatry?

It’s incontrovertible that it is the most interesting specialty in medicine. It is also the specialty of the future, because it’s the specialty where we know the least. We know the least because it’s the most complex. Our lack of knowledge is due to the fact that the brain regions which psychiatry addresses are the most complex components of human neurology. They’re the regions that deal with higher function: the parts of the brain that have the capacity to think of and plan for the future, to establish relationships, to regulate mood, to model the world and reality. These are deeply human, highly sophisticated skills which people don’t realise are neurological.They are skills erroneously thought to be purely social. If you’re a young person, and you’re interested in psychiatry, depending on where you’re training and which culture you come from, you can sometimes get the sense that people don’t think it’s worthwhile. You have to remind yourself that it’s the most gratifying and intellectually stimulating and complex subject there is. Stick to task, and to your true intentions and aims.

Any advice for aspiring writers?

Writing is a lonely area of human life, so you need to be properly determined and very focused and disciplined to do it. You will know whether you have an urge to do it. You can’t but do it, if you’re one of the people who have to do it. Don’t regard it as simply a gift; it’s a craft. It’s similar to medicine in the sense that the more you do it, the better you get at it. Therefore, you have to keep at it.

You also can’t be a good writer without reading a lot. Reading with a view to seeing how the text is put together. You are looking at the mechanics of it. That tells you something about how to think about your own composition of works.