Last Updated on June 26, 2022 by Laura Turner

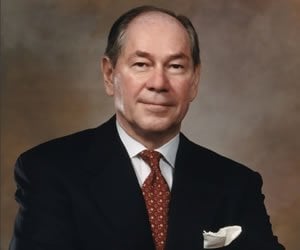

Norman J. Pastorek MD, FACS specializes in facial plastic surgery. He trained at The University of Chicago Illinois and is board certified by both the American Board of otolaryngology and the American Board of Facial and Reconstructive Surgery. He has a private practice on Park Ave in New York.

When did you first decide to become a physician? Why?

It was really by accident. I had graduated from high school and decided to go to a college in Davenport, Iowa on a whim. At that point, I was considering being an engineer, so I took all of the required math and mechanical drawing courses. Long story short, I hated it—and I did not excel at my work because I didn’t like what I was doing.

After that first year, I went back to work in a factory where I was a welder. I was content enough doing that work, so for a time I thought I would just stay on that course. It wasn’t until I ran into an old coworker who was going into medicine that I started considering other options: he asked if I liked biology and suggested I go into pre-med. So I did.

How/why did you choose the medical school you attended?

My background was highly important to my decision. Both of my parents were immigrants; my father was from Czechoslovakia and my mother from Italy. They adored America, but money was always incredibly tight—there was no one to help pay my tuition. I had to earn everything for myself from the very beginning.

By the time I was 13 years old, I was working every day at a grocery store, unloading boxcars of potatoes and trucks every night after school and on the weekends. By the 8th grade, I had exceeded my whole family in education. I earned enough money to pay tuition to go to a nearby Catholic school which offered a better education than the local public school.

I really wanted to get ahead in life and attending this better school seemed like the best route. Every day, I hitchhiked 12 miles there and back. But while working every day in a grocery store was enough to cover the tuition of a local Catholic school, there was no way I could afford to go away for college. I applied to a small liberal arts college near my home so I could live at home and work nights to pay the tuition.

I was fortunate to be accepted to the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago and got a tuition scholarship.

What surprised you the most about your medical studies?

How much I loved it. Although I fell into it initially, it became my calling. I could study all night and it wouldn’t bother me—I just loved the science and the reading which, opposite to my engineering education, in turn made the work easy for me.

I basically did nothing else for four years. I skipped out on movies, I rarely went to parties, I didn’t get involved with politics, I didn’t watch TV. Day and night, all I did was study. Those books were my life. If someone tried to discuss a TV program from that period of my life, I have no idea what they are talking about because I never turned the TV on. I was fully, and happily, focused on my studies.

Why did you decide to specialize in plastic surgery?

After finishing your third year of medical school, you begin thinking about what area of medicine you want to practice—and for me, that involved some trial and error. I thought pediatrics might work out because I enjoy children, but I realized I didn’t have the right temperament. The same realization hit when I tried psychiatry.

I was noticing the plastic and reconstructive work of those in the field of head and neck surgery and otolaryngology. It caught my interest and the rest is history. Once I got started, I fell in love. The first rhinoplasty I did came out beautifully and I just knew that’s what I wanted to do.

If you had it to do all over again, would you still specialize in plastic surgery? (Why or why not?)

Absolutely. The joy and fulfillment I receive on a daily basis is incredible. I can’t imagine doing anything else. Helping people in this way is definitely my calling.

Has being a plastic surgeon met your expectations? Why?

You have to do something in life that really makes you happy. If you’re doing something that is making you happy, that’s your life, then that’s what you should do. If you’re unhappy in your job, it will make you sick. It’ll drive you crazy, give you nightmares. But if you’re doing something, anything, that makes you happy and makes you get up in the morning excited to work, that’s perfection.

For me, that’s plastic surgery. I wake up and I can’t wait to see my patients. It has absolutely met my expectations in the best possible way. I’m as excited now, years and years later, as that college kid up all night reading medical books.

What do you like most about being a plastic surgeon? Explain.

Being able to help people and see how their lives can change is incredibly rewarding. Just today, I ran into these patients I operated on about a year ago—they came all the way from Israel to see me. The woman is beautiful and happy, she feels her results are perfect, and both were thrilled. Seeing how happy they are really triggers a lot of satisfaction for me.

What do you like least about being a plastic surgeon? Explain.

It’s not necessarily that I like it least, but being a plastic surgeon is an enormous responsibility. People come to you when they want to improve their lives and change their image. You have to pick out the people where the operation is appropriate and who would benefit from surgery. It has to be successful both physically and psychologically.

You also have to recognize those who want surgery for the wrong reasons; those who assume it will drastically change their lives or another person’s attitude toward them. I can’t make that happen. I cannot influence someone else’s opinion about another to change their life. All I can do is improve their self-image and self-confidence, helping them feel better about themselves. I cannot change the outside world through the operation, I can only change the person.

It requires a certain finesse; I have to talk to these patients correctly. When you’re first starting out, it’s easy to be talked into a surgery you maybe shouldn’t perform. It rarely happens to me anymore because I’ve been doing it for so long, but it happens to us all and results in unhappiness for both the patient and the surgeon.

What was it like finding a job in your field–what were your options and why did you decide what you did?

I know it’s probably annoying to hear, but throughout my life, things just seemed to always work out for me. I always took the path of least resistance, and it worked. From my story, it may seem like I “struggled” through medical school, but I didn’t. I was focused.

When I first began practicing, I was performing head and neck cancer surgery often. I was doing reconstructive surgery and after-cancer surgery. I began introducing trauma and aesthetic surgery and of everything I was doing, I just really loved the aesthetic aspect. So, as the years went by, the reconstructive and cancer surgeries lessened and aesthetic patients just kept coming to me. I think it’s because I loved that part of it—the universe just brought that to me.

On average: How many hours a week do you work? How many hours do you sleep per night? How many weeks of vacation do you take?

At this point in my career, I work four and a half days a week. I usually take some time off on Friday afternoons to run errands or do other things that need to be done. In terms of vacation, I need to take more! I travel frequently, but more often than not it is for lecturing. I jump from lectures on rhinoplasty in Chicago to Dallas for a meeting to Holland to perform live surgery. When I say I’m going to the Caribbean in January, it sounds like a beautiful mid-winter vacation, but the reality is that I’m going solely to teach and do many lectures. Germany and Paris are also on the calendar for teaching in 2016.

The majority of the time I take off is for giving presentations, operating, teaching, and lecturing. That doesn’t leave much room for recreational traveling. In the future, I may not teach as much, but I really do love it.

As for sleep, as I get older, I’ve definitely placed much more importance on it—I used to get away with much less than I do now. I go to bed by 11 PM and am up at 5:30 AM on the dot every morning. After I wake, I go to the gym for about an hour. By 6:30, I’m back upstairs to meditate for about 30 minutes before starting my day.

Do you feel that you are adequately compensated? Why or why not?

I absolutely do. I make a good living. I am able to support myself, my children, and my wife comfortably. I live where I want to live and am able to do what I want to do. I love being my own boss.

If you took out educational loans, is/was paying them back a financial strain? Please explain.

I am thankful everyday that I never owed a penny. Working my way through might have been difficult at the time, but I wouldn’t do anything differently. Many people don’t do it anymore, but I worked every single night of college from 5 to 9 in a hospital laboratory drawing blood and doing chemistries on patients going into surgery the next day. Even when I went to medical school, I found a job in a fraternity kitchen serving lunch and dinner and washing dishes to earn my room and board.

In your position now, knowing what you do – what would you say to yourself when you were beginning your medical career?

My previous answer covers it pretty well: focus on what you love, work hard, and try not to owe anyone money. Don’t let a loan be a burden on your life.

What information/advice do you wish you had known when you were beginning your medical studies?

Learning to say no. This can be saying no to a patient who won’t benefit from surgery, or saying no to an extra shift that will impact your studies. It can be hard to say no, particularly when you feel responsible for outcomes or you don’t want to let another person down, but it’s an incredibly important skill.

From your perspective, what is the biggest problem in healthcare today?

Insurance deductibles. Everyone pays a lot of money to be covered appropriately, but if something happens, they then have to pay off this huge deductible. They are never able to get to the point where their insurance kicks in, and it’s a real problem.

Insurance in general can be tricky for both patients and providers. From my understanding all of the new ICD-10 coding is going to present some large issues. If the codes aren’t just right, the insurance won’t pay. It has gotten to the point where they are advising physicians and medical offices to prepare themselves to take out loans to support the business while waiting for the insurance company to pay.

Where do you see your specialty in five years?

There’s been a lot of progress in recent years, and it’s only going to continue. New technology, devices, and techniques are constantly changing the game. However, there are certain, basic things that just don’t need new technology. Some of the new automated technologies are of huge cost without much benefit; I can make the same straight cut in a bone with a $100 osteotome, but they’re pushing an ultrasonic bone cutter for thousands of dollars.

I feel like you have to be discerning. Just because it’s new doesn’t always mean it’s better. If something isn’t broken, don’t try to fix it.

What types of outreach/volunteer work do you do, if any?

I do like teaching all the time. I give lectures to the medical students, and I train a fellow every year. For many years, I went to the mountains of central Mexico every fall with a team. We would work with people who had scars, trauma, and disfigurations. After coming down from the mountains, we would see as many people as we could all day on Friday and then operate all day Saturday and Sunday to hopefully take some of the weekly case burden off of the hospitals during the week. I did that for about eight years. I found that was very satisfying, but also sad.

Do you have family? Do you have enough time to spend with them?

We’ve always had dinner together every night. That was one of the things that we thought was really important when my two little girls were younger. No matter what, we would always have dinner, talk about school, talk about their life, talk about what was going on. Many families just don’t do that. Here in New York especially.

I would advise everyone to make sure you’re home at night, if at all possible. Have dinner with your kids every night, talk to them about their lives. Be present.

How do you balance work and life outside of work?

It’s important to set boundaries for yourself. It can be easy to get so wrapped up in work that the rest of your life passes you by. There is definitely a balance to be achieved between an appropriate level of focus and the ability to step away when the day is done to go spend time with your family.

What is your final piece of advice for students interested in pursuing a career in your field?

Do it because you love it. Don’t do it because you think it’s going to provide job security or any kind of prestige. Just do whatever you’re going to do so that it makes you happy in your heart and your soul. Love what you do every day and you’ll find your bliss. When that happens, everything will turn out okay.

You have to find that thing that really shakes you up. You have to love it. If you want to get up every morning to do it and go to bed every night thinking about it, you’ve found your calling.