It’s Real: The Sophomore Slump

I strolled into second year, fresh off the plane from my South American adventures and ... Read more

Written by: Adelle

Published on: October 17, 2016

Learn about medicine and how to become a physician in our articles for pre-medical students (including the MCAT), medical students, resident physicians, and practicing physicians.

I strolled into second year, fresh off the plane from my South American adventures and ... Read more

Written by: Adelle

Published on: October 17, 2016

Earlier this year SDN member bob123451 was the lucky intern starting residency on night float ... Read more

Written by: Student Doctor Network

Published on: October 13, 2016

It’s important to remember that as you prepare for and apply to medical school, there ... Read more

Written by: AAMC Staff

Published on: October 13, 2016

In an ideal world, the months before an MCAT test date would be exclusively devoted ... Read more

Written by: Cassie Kosarek

Published on: October 12, 2016

It is not just nostalgia and excitement that grips me as I am nearing the ... Read more

Written by: Butool Hisam

Published on: October 11, 2016

By Amy Rakowczyk One thing is certain during medical school: your medical spouse is going ... Read more

Written by: Amy Rakowczyk

Published on: October 6, 2016

When did you first hear about medical scribes? I first heard the term ‘medical scribe’ ... Read more

Written by: Alyssa Kettler

Published on: October 4, 2016

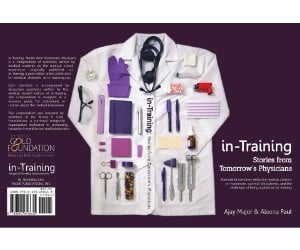

In early 2012, medical students Ajay Major and Aleena Paul started in-Training.org, a website dedicated ... Read more

Written by: Student Doctor Network

Published on: September 29, 2016

Republished with permission from here. Earlier in the summer, I was speaking with a friend ... Read more

Written by: Brent Schnipke

Published on: September 28, 2016

Central to the skillset of every physician is the differential diagnosis; this is the process ... Read more

Written by: Brent Schnipke

Published on: September 26, 2016

Follow these six steps to achieve Shelf Exam success

Written by: ExamGuru

Published on: September 21, 2016

Before medical school, the dream of becoming a physician involves helping people and curing disease. ... Read more

Written by: Universal Notes

Published on: September 20, 2016

In Part One of this series, we discussed post-baccalaureate pre-medical programs for career-changers (i.e. those who have ... Read more

Written by: Cassie Kosarek

Published on: September 14, 2016

Two days before interviewing at the medical school I now attend, I couldn’t get out ... Read more

Written by: SDN Staff

Published on: September 12, 2016

Recognizing the connection between lab work and surgery What surprised me the most during my ... Read more

Written by: Michael Mehlman

Published on: September 7, 2016

Updated September 6, 2021. The article was updated to correct minor grammatical errors. Expectations. The ... Read more

Written by: Amy Rakowczyk

Published on: September 1, 2016

A friend of mine studied film in college and subsequently found himself working as a ... Read more

Written by: Ryan Hickey

Published on: August 31, 2016

Central to the skillset of every physician is the differential diagnosis; this is the process ... Read more

Written by: Brent Schnipke

Published on: August 29, 2016

The path to becoming a doctor can feel daunting. For those of us that don’t ... Read more

Written by: Megan Riddle

Published on: August 17, 2016