The sub-internship is a crucial rotation for all medical students, no matter which specialty they plan to pursue. During this transitional phase in their clinical training, students begin to assume more independent responsibility for patient care. A sub-internship introduces students to life as residents, and it is often a source of recommendation letters for the residency application process. Below are my top tips for success during your sub-internship.

physician

Student Loan Forgiveness for Medical Students

Many medical students cheerfully expect to be earning a generous income as they begin their medical practice. But while it is true that that, according to the Medical Economics website that in 2014, 7 of the 10 top-paying jobs were in the medical profession, the issue of course is far more complicated than that. The American Association of Medical Colleges estimates that a four-year medical education at a private school today will cost around $278,455 dollars while a public one runs only slightly below that at $208,868. And the average medical student will be around $180,000 in debt at the time of their graduation. Around 20% will have debt in excess of $250,000.

These numbers can seem staggering. Fortunately, there are programs available to medical students which not only get them out from this monumental debt, but help underserved communities across the country and improve access to quality medical care for some very vulnerable patient populations.

The Right Time to Lose a Patient

Republished with permission from here. Although there is really never a right time to die … Read more

What You Should Know: Lies in the Patient-Doctor Relationship

What You Should Know is an ongoing series covering a range of informational topics relevant to current and future healthcare professionals.

It happens to every medical student sooner or later – the realization that their patient has lied to them. Especially for students, who are just beginning to gain clinical experience, this realization can come as a shock. A sense of betrayal, anger or even the desire for retribution can set in, all of which can be damaging to the doctor-patient relationship.

These emotions aside, it might help student doctors dealing with the nature of this reality to understand where deception enters into the therapeutic relationship – as well as how and why people lie in a clinical setting and what the doctor can do about it.

The Importance of Disability Insurance for the Young Physician

The thrill and responsibility of holding someone’s life in your hands, the ability to act under pressure, and the satisfaction of doing good in the world—these are among the qualities that attract people to the medical profession. In a culture that’s quickly diminishing the value of established professions, there’s still a universal appeal to becoming a doctor.This doesn’t mean seeking a career in medicine is without its obstacles. The importance of a thorough education—at least four graduate years—cannot be understated. Add in the time it takes to complete an internship and a residency, and it’s easy to see why a medical path can be too daunting for many. On average, it takes about 11 years for a medical student to become an independent doctor. If students begin medical school in their 20s, they won’t begin to see patients as a physician until they’re in their 30s. Add to that an average price tag of $166,000 in student loans for medical school, and even the most gung-ho medical students begin to balk. Suffice it to say, a career in the medical field is a huge time and financial investment.

The Art and Science of Narrative Medicine

Many medical students, even those with a background in the liberal arts, may have a hard time conceptualizing the role that the humanities–in particular, the art of the narrative–may have to play in clinical practice. However, a relatively new theory and practice of medicine, called narrative medicine, is beginning to take root and contains elements of both medical and language arts.

What is Narrative Medicine?

The phrase “narrative medicine” was coined by Dr. Rita Charon, one of the founders of this movement, which began to develop in the 1990’s in response to the perception of detachment and over-professionalism in medical practice. Dr. Charon wanted to explore new ways that medical practice could become more humanized and emotive– and lead to greater satisfaction with the clinical relationship for both doctors and their patients. In her definitive article, entitled “Narrative Medicine: a Model for Empathy, Reflection, Profession and Trust” which appeared in JAMA in 2001, Charon introduces her readers to this new concept by noting that “adopting methods such as close reading of literature and reflective writing allows narrative medicine to examine and illuminate four of medicine’s critical narrative situations: the physician and patient, physician and self, physician and colleagues and physician and society…By bridging the divide that separates physicians from patients, themselves, colleagues and society, narrative medicine offers fresh approaches for reflective, empathic and nourishing medical care.”

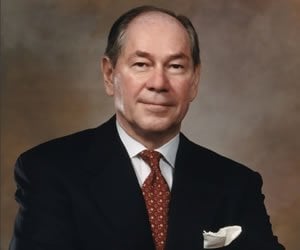

20 Questions: Norman Pastorek, MD – Plastic Surgery

Norman J. Pastorek MD, FACS specializes in facial plastic surgery. He trained at The University of Chicago Illinois and is board certified by both the American Board of otolaryngology and the American Board of Facial and Reconstructive Surgery. He has a private practice on Park Ave in New York.

When did you first decide to become a physician? Why?

It was really by accident. I had graduated from high school and decided to go to a college in Davenport, Iowa on a whim. At that point, I was considering being an engineer, so I took all of the required math and mechanical drawing courses. Long story short, I hated it—and I did not excel at my work because I didn’t like what I was doing.

After that first year, I went back to work in a factory where I was a welder. I was content enough doing that work, so for a time I thought I would just stay on that course. It wasn’t until I ran into an old coworker who was going into medicine that I started considering other options: he asked if I liked biology and suggested I go into pre-med. So I did.

On The Shoulders of Giants: Tips for Aspiring Female Surgeons

While there were many engaging sessions held at the 2015 UC Davis Pre-Health Conference, a few stood out for being exceptionally inspiring. Dr. Lisa Lattanza’s lecture, “How to Be a Successful Female Surgeon”, was one of these standouts.

This isn’t surprising, considering Dr. Lattanza’s pedigree. The chief of Hand, Elbow & Upper Extremity Surgery at UCSF Medical Center, she is known both for her surgical skills and her inexhaustible efforts to encourage and mentor the next generation of female surgeons. She is the president and co-founder of The Perry Initiative, a Bay-area-based foundation which provides educational and experiential opportunities for young women (primarily high-school and early-college-aged) interested in orthopedic surgery – a project which recently earned her the prestigious Jefferson Award for public service.

20 Questions: Natalie E. Azar, MD – Rheumatology

Dr. Natalie E. Azar is assistant clinical professor of medicine and rheumatology at the Center for Musculoskeletal Care NYU Langone Medical Center, as well as medical contributor to powerwomentv.com, member of the admissions committee for NYU School of Medicine, and instructor of the Physical Diagnosis Course at NYUSoM. She received a bachelor’s degree in psychobiology from Wellesley College (1992), where she was a Phi Beta Kappa (1991), Durant Scholar (1992), and Who’s Who Among American College Students (1991). Azar received her Doctor of Medicine from Cornell University Medical College (1996), with honors for academic excellence in anesthesiology (1998). Dr. Azar completed both an internship and residency in internal medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center (1996-97, 1997-99), and a fellowship in rheumatology at Hospital for Joint Disease, New York University Langone Medical Center (1999-2001).

Hysterectomy or SSRIs?

Reposted from here with permission She was a petite, otherwise well-appearing woman, apprehensively sitting at the edge … Read more

Balancing Professional School and Life

Professional school is hectic. Very hectic. Most programs require the dedication that is equivalent to … Read more

Getting to Yes: Crafting a Resume for the Medical Field

Since the medical field is full of a wide variety of job opportunities, it is … Read more

Choosing a Specialty: The Generalist vs. the Early-Committer

Many students arrive at medical school with a bias that their liberal arts education has instilled, namely, that they should survey everything before deciding on their specialty. Before medical school, students matriculate at colleges that pride themselves on providing a diverse exposure to a variety of subjects: Computer science majors experience the canon of Great Literature before pursuing a life of code, and English majors can take “Physics for Poets.”

For a generalist student sampling from the buffet of medicine, it can be jarring to sit in lecture next to a classmate who declares on the first day of school that she intends to become an orthopedist. These early-committers appear to have whittled down their choices from day one. They magically become apprentices to a faculty member in their chosen specialty by the first quarter, have a publication by their first year, and seem to possess an intuitive roadmap for applying to residency that the generalist cannot read.

20 Questions : Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD, Radiation Oncology

Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD, is a radiation oncologist with Massachusetts General Hospital, and she divides her time among clinic research in health equity and hematologic malignancies, teaching as assistant professor of radiation oncology at Harvard Medical School, and a clinical practice treating patients with lymphoma, leukemia, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome and other blood cell dyscrasias, and breast and gynecologic malignancies.

Dr. Winkfield received her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from Binghamton University (1997), and her PhD in pathology (2004) and MD (2005) from Duke University. She completed an internship in internal medicine at Duke and a residency in radiation oncology at Harvard. Dr. Winkfield co-founded and directs the Association of Black Radiation Oncologists, and she’s been published in numerous journals, including the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Journal of the National Medical Association, International Journal of Radiation Oncology – Biology – Physics, Oncology, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, and New England Journal of Medicine. She also currently chairs the Health Access and Training Subcommittee for the American Society For Radiation Oncology and is chair-elect of the Health Disparities Committee for the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The Risk Involved in Going to Medical School (and How You Can Subvert It)

Most people wouldn’t normally think of medical school as a risky investment. Sure, there are … Read more

The Med-Peds Residency: Big and Small, We Care for Them All

As third year medical students you’re rotating through your general specialties and you think you’re seeing familiar faces but in new places. Isn’t that your newborn nursery resident who assigned APGAR scores, now leading the code in the medical ICU? Some of you may have had similar déjà vu experiences but rest assured, your mind isn’t fooling you. At 79 programs across the USA and Puerto Rico, Combined Internal Medicine and Pediatric residents walk (briskly) through the halls of the hospital carrying both PALS and ACLS cards in our coat pockets. Our minds have been shaped to think broadly and decisively. We carry an air of calmness from our critical care rotations yet we know when to appropriately turn to our goofy side to connect with our patients. Through four years of versatile training, we are training to be the 21st century physician.

The Combined Internal Medicine-Pediatrics (commonly referred to as “Med-Peds”) is a four-year residency-training program that leads to dual board certification in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics. While there are many combined training programs offered in the US, the Med-Peds residency is by far the most ubiquitous and popular program available. During the four years of training, residents undergo a rigorous schedule of rotations ranging from adult and pediatric wards, MICU, PICU, NICU, CCU, Med-Peds clinic and specialty electives. By graduation, residents will have completed a total of 2 years of adult and 2 years of pediatric training. The frequency at which residents switch from one “side” to another changes depending on the individual residency program. The end product is the same: Individuals who are prepared to deal with acute, complex, chronic and preventive care for both adult and pediatric medical conditions. The broad training creates an endless list of career possibilities. We each carve out a niche that best fits the career interest we have in mind.

Five Ways to Make Your Audition Rotation in Anesthesia (or Other Specialty!) a Success

It is that time of year again. Medical school students across the country are preparing applications for residency and pursuing audition rotations at residencies they are hoping to woo into an interview and hopefully to match into their program.

Any audition rotation is a challenge. This is especially true for the anesthesia audition rotation. For medical school students who look great on paper, the audition rotation can either confirm they are a great candidate or confirm the program should not interview/rank them. For medical school students who do not have a stellar record, the audition rotation can open up doors.

How to ace your first patient encounter

As a medical student, you spend four years of college and the first two years of medical school studying non-stop for what feels like thousands of hours, cramming your brain with knowledge. But when the time comes to conduct your first face-to-face patient encounter, your confidence is rocked by the challenge of having to establish rapport, extract all the relevant medical history, and complete a physical exam, all while showing compassion, answering patient questions, and developing a differential diagnosis list and treatment plan in 30 minutes or less. Clinic is even worse with a meager 12 minutes scheduled for each patient encounter.

Physician Employment Contracts: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

In both hospital[1] and group practice settings, physicians are regularly asked to sign employment contracts that the group or hospital may describe as “standard”. While physician employment contracts can define the terms of the employment relationship in helpful ways, they can and often do contain clauses and obligations that may have a long-lasting impact on the physician. When negotiating a contract with a potential employer, physicians are well advised to take a hard look at key contract terms, including termination provisions, non-compete clauses, professional liability insurance terms and indemnification obligations, and negotiate to remove or revise overly burdensome terms prior to the start of the employment relationship.

Graduation Day Thoughts on Student Debt

Memorial Day and Mother’s Day are May’s official holidays, but for millions, graduation day is May’s biggest celebration—as momentous as a wedding or birth. Graduation creates memories of a proud family gathering, celebrations with classmates, and the inspiring message from a charismatic commencement speaker.

I’ve had my share of graduations—high school, college at Cornell University, medical school at GW, grad school at Hopkins. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) President Jordan Cohen addressed my medical school graduation. I had no idea who he was. A decade later, I went to work for him, and the AAMC has been my professional home ever since.